- Home

- Leona Deakin

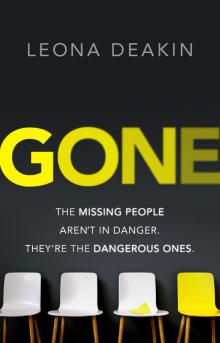

Gone

Gone Read online

Gone

LEONA DEAKIN

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

Chapter 66

Chapter 67

Chapter 68

Chapter 69

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Leona Deakin started her career as a psychologist with the West Yorkshire Police. She is now an occupational psychologist and lives with her family in Leeds. This is her debut thriller.

For my sisters, Elizabeth and Joanne.

Thank you for inspiring me to write.

We are all worms. But I do believe that I am a glow-worm.

Winston Churchill

When evening closes Nature’s eye

The glow-worm lights her little spark

To captivate her favourite fly

And tempt the rover through the dark.

James Montgomery

1

Fourteen-year-old Seraphine Walker’s blonde hair fell in pretty ringlets. She wore a tight-fitting school jumper and a short skirt. There was something immediately enticing about her. But, like glow-worms shining hypnotic torches to draw in their prey, Seraphine Walker was not all that she seemed.

The school bell rang. Seraphine dropped her pencil. It hit the ground with a soft clack and tiny droplets of blood splattered from its point across the polished wooden floor. The caretaker lay beside the pencil, his hands to his neck and a crimson circle oozing from his crumpled body. He was almost certainly dying.

It looked beautiful. Was that disrespectful? Probably. But so was standing here watching every breath produce bubbles of blood that splashed across his chin.

Seraphine knew she should look away. But she couldn’t. It was fascinating. She was struck by the urge to kneel down, to get closer, to see if the wound was neat where her pencil had met his skin, or loose and ragged. Logic told her it should be the former. She’d stabbed him quickly and decisively, so it should be a clean wound. She wanted to know for sure. Just a little bit closer.

‘Seraphine? Seraphine?’

Mrs Brown was running across the sports hall. The Art teacher’s huge bosom bobbed up, down, up, down, as her corduroy skirt whooshed against her boots. Her expression was one of panic and fear. Seraphine was surprised. She’d expected anger. Seraphine looked at Claudia, who sat sobbing, her arms wrapped around her legs and her head shaking against her knees. Mrs Brown sped past her without acknowledgement. Claudia raised her head and cried louder. Her eyes were red and her cheeks streaked with tears, but her expression was strange. No relief whatsoever.

Seraphine was good at reading people. Really good. But she couldn’t always understand them. Why did they cry? Why did they scream? Why did they run?

And so she watched. She studied them. She mimicked. And fooled.

2

Coffee in hand and pyjamas still on, Lana sat at the small desk on the landing, ignoring the view of north London and staring instead at the laptop screen in front of her. She completed the day’s trending Facebook quiz – What kind of coffee are you? – and then sat back, hugging her mug in both hands and waiting for the results to load. The screen was too bright and the curser pulsed to the beat of her aching temples. A more patient person would find the control settings and adjust the contrast, but Lana simply yanked out the power cord, sending the laptop into power-save mode and making the screen three shades darker.

The result was in: You are a double espresso – too hot and strong for most to handle. Lana liked the sound of that. Her daughter used phrases that were far less complimentary, with words like irresponsible, crazy, a mess. Jane would judge her for the wine bottle in the kitchen bin and the vodka at her bedside. At Jane’s age Lana had been a promiscuous drug-user with at least three arrests for petty crime under her belt, so, compared with what Lana had put her own mother through, a judgemental, boring daughter was no big deal. A bit disappointing, but no big deal.

Lana shared the quiz result with her Facebook friends and Twitter followers. Marj had posted a quote about good things happening to good people. Seventeen others had liked it. Lana typed a swift response – Tell that to the 39 people killed in the Istanbul nightclub shooting – and pressed Enter. People could be such dim, optimistic idiots.

There was a knock on the door. Lana padded downstairs with bare feet, wondering what type of person ignores a perfectly working doorbell to ram their meaty fist against a block of wood. Instant coffee served with a truckload of milk and two sugars, she concluded as she opened the door. There was nobody there. Lana checked for a delivery card or parcel left on the doorstep and found neither.

‘Stupid kids,’ she muttered under her breath as she went to boil the kettle again.

In the kitchen, she spooned ground coffee into the cafetière, filled it with water and then rinsed her mug in the sink. In the garden a large blackbird strained to pull its wriggling breakfast out of the ground. For a moment it looked as if the worm might have the upper hand, but then the bird replanted its feet a couple of times in a kind of avian death dance and, ping, out the worm sprang. Lana turned to fetch milk from the fridge – and there it was.

At the end of the hall by the front door a small white envelope lay on the carpet. It had been pushed against the wall when she’d answered the knock. Lana went to pick it up and turned it over. It shimmered as it moved. Her name was printed on the front, embossed in silver foil.

Her phone started to ring. She rooted for it in her pocket and checked the screen.

‘Hi, babe,’ she said, aware that her voice was hangover-husky.

‘I wanted to wish you a Happy Birthday,’ said Jane.

‘Go on then,’ said Lana.

There was a momentary pause. ‘Happy Birthday, Mum. What have you got planned for today?’ This was code for Don’t spend all day in the pub.

Lana ignored her daughter’s question. ‘Is this card from you?’

Another pause.

‘The card that’s just arrived,’ Lana continued. ‘Is it from you?’

‘What card?’

‘Not to worry. Are you home normal time? Shall we go out

for tea?’

Jane said something with her hand over the mouthpiece, then, ‘Got to go, Mum. See you later. Have a nice day.’

A skinny single-shot latte – that would be Jane. Not too much caffeine, not too much fat; a sensible, boring coffee. Lana picked up the envelope. She lifted the flap and removed a white card. On the front it said Happy 1st Birthday.

Was it a joke? She didn’t get it.

She opened it. Inside, it said:

YOUR GIFT IS THE GAME.

DARE TO PLAY?

Lana smiled. ‘What sort of game are we talking about?’ In the middle of the shiny white card a long strip of tissue paper contained a URL and an access code. Lana reached for her phone, opened the website and followed the instructions. A plain white webpage loaded and then in the same silver writing:

Hello, Lana,

I’ve been watching you.

You’re special.

But you know that already, don’t you?

The question is …

Lana scrolled down.

Are you prepared to prove it?

Underneath was a large red button stamped with the word PLAY. Then another phrase appeared. It scrolled across the screen, from right to left, again and again.

I dare you.

Like every player who had gone before and every player who would follow, Lana pressed the button. She felt no fear. She didn’t stop to consider the consequences or to ponder the mysterious card. She simply wanted to know what came next.

3

Seraphine sat in the small, windowless room at the police station wondering if her answers sounded convincing, if they were normal. She had no idea how a normal person would talk about this sort of thing. She was relying on police dramas, books and her own imagination.

‘So tell us again, Seraphine, how did you come to be in the sports hall this morning?’ Police Constable Caroline Watkins had asked this question twice already. Her voice was high pitched and girly. She had her dark hair in a neat bun at the nape of her neck. Her make-up was thick but immaculate and each time she repeated a question her left eye twitched.

Seraphine shrugged. ‘We were just bored,’ she said for the third time.

‘And you said the caretaker, Darren Shaw, followed you and Claudia Freeman?’

Seraphine nodded.

Watkins tilted her head towards the recording equipment.

‘Yes,’ said Seraphine.

‘And the pencil?’

‘It was in my pocket.’

Watkins looked straight at Seraphine. ‘Oh yes,’ she said. ‘From your Art class.’ The smallest of smiles touched her lips.

‘No,’ said Seraphine. ‘DT. Design Tech.’

‘Of course. My mistake.’ PC Watkins pretended to amend her notes. ‘So, Mr Shaw approached Claudia in the sports hall. You said she was in trouble. What do you mean by that?’ Watkins’ eye twitched.

Seraphine repeated her response, exactly the same as before. ‘He was holding her by the back of her neck and he had his hand down her top.’

‘And you’re sure this wasn’t consensual?’

Seraphine paused for a moment to consider what that little bitch Claudia might have said. They were friendly, but Seraphine knew Claudia resented her popularity. How far would Claudia go to undermine her?

‘Are you sure he was forcing Claudia against her will?’ Watkins said.

‘She’s fifteen,’ Seraphine replied, insulted at the implication that she didn’t know the meaning of the word ‘consensual’.

Watkins’s cheeks flushed.

Seraphine’s mother had been sitting in silence, as instructed – she was such an obedient sap – but now she spoke up. ‘What are you implying?’ she demanded, uncrossing her arms. ‘We are a good family. My daughter would never hurt anyone. This man frightened her and she simply defended herself.’

‘Is that right, Seraphine? Were you frightened?’ asked Watkins.

‘Yes.’

‘He let go of Claudia and attacked you?’

‘Yes.’

‘And you lashed out with the pencil, in your own words, hoping to scratch him?’

‘Yes.’ Seraphine did not elaborate.

Watkins held Seraphine’s eye.

She doesn’t believe me, Seraphine thought. Dropping her gaze and hunching her shoulders, she sank down in her chair and picked at the skin around her fingernails. I’m a fourteen-year-old girl and I’m scared. I didn’t mean to hurt anyone. I was just trying to help my friend and now I’m being interrogated.

For a moment she worried she’d failed to pull it off. Maybe her posture was wrong or her expression not quite right. Police officers were trained to spot a fraud.

But then Watkins folded up her paperwork. ‘OK, that’s enough for now. We’ll take a break and PC Felix here will show you where the canteen is.’ Watkins looked at Seraphine’s mother. ‘Something to eat will help with the shock.’ Then she looked back at Seraphine, her smile warm. ‘And then we’ll speak again.’

Seraphine nodded. I’m a vulnerable teenager in shock. I’m a vulnerable teenager in shock. She found it helped to repeat the words in her head.

Watkins stood and turned away. Seraphine relaxed. This was going to be a breeze.

4

The second hand of the large consulting-room clock stuttered towards nine. Sitting upright in her chair, Dr Augusta Bloom watched it, feeling each tick bat away her anxieties, the things that might distract her from focusing on another person for a full hour. She knew this session would be challenging. She’d read the notes and knew what to expect. A traumatized victim called upon to defend actions that weren’t intentional but primal.

Tick.

Tick.

Fourteen. You should have one foot still in childhood at fourteen. Innocence should drift away, little by little: Santa and the Tooth Fairy first; then the realization that your parents are flawed; then that people can be selfish; and finally that the world itself can be unfathomably cruel. Childhood needs to unravel slowly so that the mind can adjust. When it’s ripped away in one brutal moment, it leaves behind the silhouettes of denial, anger and, ultimately, despair.

Bloom didn’t have the power to turn back the clock and remove the trauma. But she could try to amplify the light inside a child’s mind and turn down the volume of their distress.

Seraphine paused at the door to the small room and evaluated Dr Bloom. The woman sat in a high-backed chair with wooden arms. She had cropped hair the colour of oatmeal and wore black trousers and a green V-neck jumper that looked neat and smart. On her feet she wore flat black shoes; Seraphine’s mother would describe them as sensible. The psychologist’s feet only just touched the floor.

She’s short, like me, thought Seraphine. That could come in useful.

‘Hello, Seraphine,’ said Dr Bloom. ‘Come on in. Take a seat.’ She kept her hands in her lap, clasped around a small black book. She waited for Seraphine to sit and then continued, ‘How are you feeling today?’

Seraphine blinked a couple of times. ‘OK,’ she said. It was a safe answer.

‘OK,’ repeated Dr Bloom. ‘Do you know why your mum has asked me to speak with you?’

‘Because of the caretaker.’

Dr Bloom nodded. ‘You know I’m a psychologist?’ Bloom waited for Seraphine to acknowledge her question, then said, ‘I work with young people who’ve been accused of committing a crime.’

‘You work for the police then?’

‘Sometimes. Although I mainly work with solicitors and their clients, or youth-offender teams, usually in preparation for a trial. But your mother has asked me to speak to you today because she’s concerned about the effect of your recent experience. So I’m here to help you make sense of it. We’ll take things at your pace. There’s a glass of water and some tissues here, and if you wish to take a break at any point, just say and we will.’

Seraphine looked at the box of tissues. I’m expected to need them, she thought. ‘What do I call you?’

&nbs

p; ‘Dr Bloom will be fine. I understand you’re quite a capable student and your teachers think you have a great deal of potential. Do you enjoy school?’

Seraphine shrugged.

‘According to your mother, you’re an accomplished athlete. She tells me you’re in the netball team and have played badminton for the county. Is that correct?’

Seraphine shrugged again.

‘And you took the lead in last year’s school production, so quite the all-rounder.’

Seraphine shuffled in her chair. She needed to get a grip. She was acting like one of her stupid friends. She looked at Dr Bloom sitting straight-backed, her feet neatly side by side and her hands in her lap. Seraphine sat up. ‘I’m good at Science and Maths.’

Dr Bloom nodded.

‘And I enjoy sports.’ She wiggled her right foot into place directly below her right knee.

‘And you’re an only child. Are you close to your parents?’

‘Very.’

‘That’s good.’ Dr Bloom smiled as though she was genuinely pleased by this response. ‘Can you tell me what you mean by “very”?’

Seraphine moved her left foot into position beside her right. ‘And I also enjoy Design Tech, because Mr Richards is a good teacher.’ And he really, really sharpens his pencils.

‘I see.’

‘Are you a medical doctor?’ Seraphine asked, as she folded her hands over her thighs.

‘No, but I have a PhD in Psychology. Do you know what that is?’

Seraphine nodded. ‘Where did you study? I don’t know whether to bother with university. It seems like a waste of time; I could just get on and earn some money. What do you think?’

‘Would you say that you’re closer to your mother or to your father?’

Neither, she thought. ‘Both,’ she replied. ‘Equally.’

‘And have they been supportive since the attack?’

Of each other. Like they were the bloody victims. Seraphine masked her irritation with a smile. ‘They’ve been fabulous.’

Gone

Gone